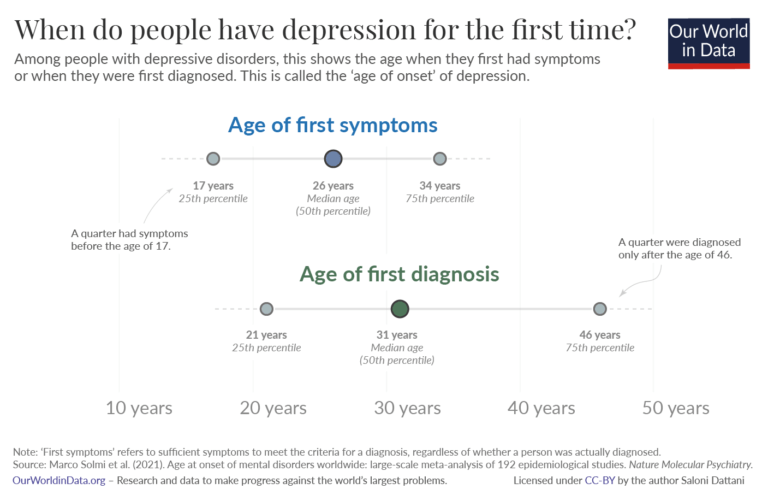

There’s been a disconnect for the longest time regarding when people had their initial symptoms for depression, and when they made a concerted effort to receive professional diagnosis and treatment (Dattani, 2022).

Members of the public may have feared being ostracized if others found out they suffered from a mental health condition (Community Reach Center, 2019). They may have thought their symptoms would miraculously disappear. To expand further, they may have been unaware of the procedures in obtaining mental health services, while others may not have had mental health services readily available in their locale (Community Reach Center, 2019).

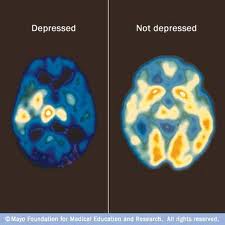

Regardless of the explanations for not getting mental health services, a mental health condition is probably the most intrusive ailment a person could ever encounter because the brain controls the entire body. As a result, the longer depression goes untreated the greater the chances for a brain chemical imbalance.

The Mayo Foundation For Medical Education And Research (2022) provides images [Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scans] of a brain under the influence of depression, and what a healthy brain looks like.

Consequently, the person who could have obtained early diagnosis and been placed on a psychotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) treatment program (World Health Organization, 2021, and National Alliance On Mental Health, 2017), now has to be placed on psychotropics because they waited too long to seek help.

Depression can shrink the brain (i.e., the brain is under assault from depression), which can interfere with the natural flow of neurotransmitters (Amiel, 2022) and (Davey, 2015).

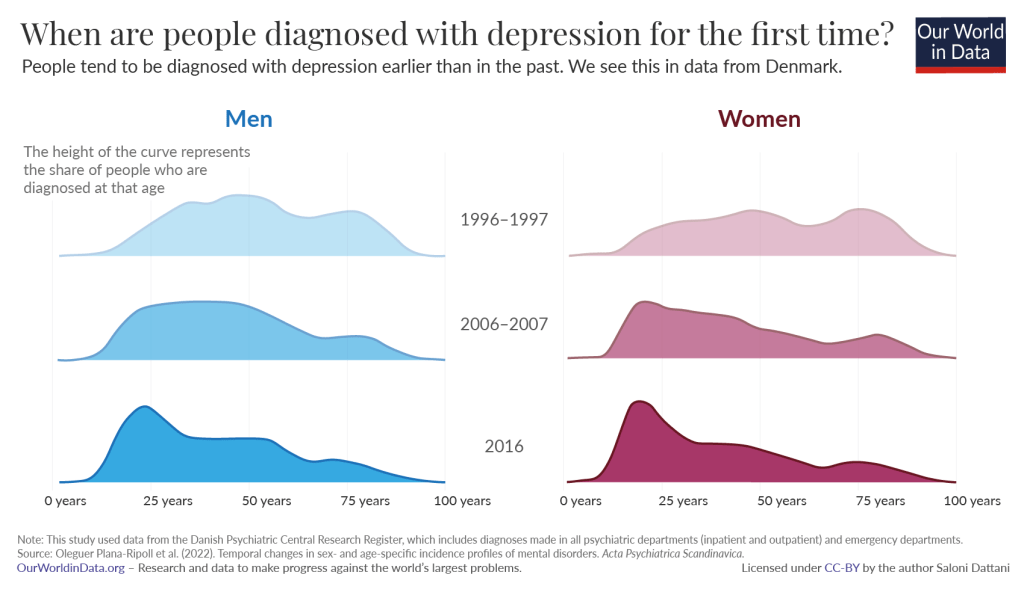

As the years progress, more people are getting early diagnosis for symptoms associated with depression, and doing so in earlier periods of their lives (Dattani, 2022). This acceptance can be considered a brand of preventative treatment by health consumers: People who take an active role in maintaining good health, and taking steps in avoiding a current condition from becoming worse (Health Consumers NSW, 2019).

Vikki

References

Amiel, M., M. D. (2022). What Happens To The Brain During Depression? Retrieved From https://www.transformationstreatment.center/treatment/what-happens-to-the-brain-during-depression/#:~:text=Depression%20causes%20the%20hippocampus%20to,of%20cortisol%2C%20the%20amygdala%20enlarges.

Community Rearch Center. (2019). Why People Don’t Seek Treatment For Depression. Retrieved From https://www.communityreachcenter.org/news/why-people-dont-seek-treatment-for-depression/

Dattani, S. (2022). At What Age Do People Experience Depression For the First Time? Retrieved From https://ourworldindata.org/depression-age-of-onset#:~:text=As%20the%20data%20shows%2C%20on,later%2C%20at%2031%20years%20old.

Davey, M. L. (2015). Mental Health. Chronic Depression Shrinks Brain’s Memories And Emotions. Retrieved From https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jun/30/chronic-depression-shrinks-brains-memories-and-emotions

Health Consumers NSW. (2019). Who Is A Health Consumer? and other definitions. Retrieved From https://www.hcnsw.org.au/consumers-toolkit/who-is-a-health-consumer-and-other-definitions/#:~:text=Health%20Consumers%20are%20people%20who,the%20service%20in%20the%20future.

Mayo Foundation For Medical Education And Research. (2022). PET Scan Of The Brain For Depression. Retrieved From https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/pet-scan/multimedia/-pet-scan-of-the-brain-for-depression/img-20007400#:~:text=A%20PET%20scan%20can%20compare,brain%20activity%20due%20to%20depression.

National Alliance On Mental Health. (2017). Depression. About Mental Health. Retrieved From https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions/Depression

World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. Key Facts. Retrieved From https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

Endnotes

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2021). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

The studies included in this meta-analysis measured this age in different ways. Some studies looked at the age when symptoms of the disorder began, some looked at when they were first diagnosed, and others looked at when they first received treatment for the disorder or were first hospitalized for it. The median age of onset for some disorders, such as substance use disorders, mood disorders and anxiety disorders was earlier when it was measured by first symptoms than when it was measured by first diagnosis or first hospitalization. - Medici, C. R., Videbech, P., Gustafsson, L. N., & Munk-Jørgensen, P. (2015). Mortality and secular trend in the incidence of bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.032

Mauz, E., & Jacobi, F. (2008). Psychische Störungen und soziale Ungleichheit im Geburtskohortenvergleich. Psychiatrische Praxis, 35(07), 343-352. https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-2008-1067557

Scott, J., Etain, B., Azorin, J. M., & Bellivier, F. (2018). Secular trends in the age at onset of bipolar I disorder – Support for birth cohort effects from international, multi-centre clinical observational studies. European Psychiatry, 52, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.04.002

Plana‐Ripoll, O., Momen, N. C., McGrath, J. J., Wimberley, T., Brikell, I., Schendel, D., Thygesen, M., Weye, N., Pedersen, C. B., Mors, O., Mortensen, P. B., & Dalsgaard, S. (2022). Temporal changes in sex‐ and age‐specific incidence profiles of mental disorders—A nationwide study from 1970 to 2016. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, acps.13410. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13410 - Plana‐Ripoll, O., Momen, N. C., McGrath, J. J., Wimberley, T., Brikell, I., Schendel, D., Thygesen, M., Weye, N., Pedersen, C. B., Mors, O., Mortensen, P. B., & Dalsgaard, S. (2022). Temporal changes in sex‐ and age‐specific incidence profiles of mental disorders—A nationwide study from 1970 to 2016. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, acps.13410. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13410

- Schomerus, G., Schwahn, C., Holzinger, A., Corrigan, P. W., Grabe, H. J., Carta, M. G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2012). Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Evolution of public attitudes. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125(6), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01826.x

Angermeyer, M. C., Matschinger, H., & Schomerus, G. (2013). Attitudes towards psychiatric treatment and people with mental illness: changes over two decades. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2), 146-151. - While 0.4% of children and adolescents were in contact with a psychiatric department in 2001, that figure was 3.3% in 2018. The Danish Health Data Authority. (2019) Key numbers about health care in Denmark (in Danish). https://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/tal-og-analyser/analyser-og-rapporter/sundhedsvaesenet/noegletal-om-sundhedsvaesenet

Schmidt, M., Schmidt, S. A. J., Adelborg, K., Sundbøll, J., Laugesen, K., Ehrenstein, V., & Sørensen, H. T. (2019). The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: From health care contacts to database records. Clinical Epidemiology, Volume 11, 563–591. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S179083 - Babatunde, G. B., van Rensburg, A. J., Bhana, A., & Petersen, I. (2021). Barriers and Facilitators to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Global Social Welfare, 8(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-019-00158-z

Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., Rohde, L. A., Srinath, S., Ulkuer, N., & Rahman, A. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

You must be logged in to post a comment.